It takes courage to buck conventional wisdom and do something different, but for the farmers in the Stephenson family it was that enquiry-based learning that has been at the heart of their farming philosophy through the generations.

The late conservationist and Waikato farmer Gordon Stephenson described in his memoirs, Journey, how his father’s reputation was once called in to question by the locals when he was seen cutting his hay very early, throwing it in a ditch and pouring treacle on it. Obviously, a very early trial of the then-novel concept of silage.

His daughter, Lynn Smith, says this desire to experiment is definitely generational. “There is a scientific kind of gene running through the family. His father and grandfather were just like him. They weren’t content with just being on the farm. They were out in the community, learning and sharing knowledge.

“I remember Gordon talking of one farmer who had really good production and Gordon asked him, “What’s your secret?” He always wanted to know what was working.”

“And the farmer said, ‘I love my cows’. And that that was it. He loved his cows. Gordon could see a lot of farmers were like that.”

When he was farming, Gordon was determined to raise the issue of energy efficiency on farms. Phillipa Crequer, who worked with Gordon as the coordinator for the Waikato Farm Environment Awards, says he was sure he could come up with a formula for the whole farm and find out how much energy it really took to run a farm.

“He worked with Massey University on a whole farm energy project, and was able to show that the more trees you had on your farm, the more energy efficient you were.”

In his memoirs, Gordon describes raising the issue of energy efficiency long before it was common usage. He writes, “On the farm, I had designed an energy-saving system in the dairy shed which extracted the heat from both the warm milk and from the operation of the chiller that cooled the milk flowing into the vat. With this, we were able to heat the washing water to a temperature that required very little additional energy to bring it up to the necessary temperature for washing the entire milking machinery. There were big savings.

This system was then forbidden by the dairy company because ‘it negated their insurance with the chiller manufacturers’. It was almost 25 years before similar energy-saving systems became acceptable, or even deemed desirable.”

As he told University of Waikato graduates in a graduation address delivered when he was in his eighties, from a young age he was “infected” with the stimulating subject of science. Even seven decades later, he still had some of the original nature magazines he used to pore over. At Sanctuary Mountain (Maungatautari Ecological Island) he was heavily involved, even into his eighties, supporting the research being undertaken on the mountain to assess the effectiveness of a predator-proof fence and the breeding successes of reintroduced species. He was an early advocate for taking action on climate change and continued to be concerned about its implications for farming and for the natural environment.

When Gordon and Celia bought a block of land adjacent to their dairy farm in Waotu, South Waikato, as their ‘retirement’ block, they put in place the sustainability principles they had been thinking about for a long time. He writes, “We decided that every paddock should have shade and shelter. This should be a mixture of harvestable exotics and native understory. Steeper slopes should be in trees, rather than trying to graze them. We looked around for a quicker growing, ground durable timber, but our trial with chestnuts failed.

“We planted two plots of Cupressus, macrocarpa and lusitanica. We put in about forty nut trees. Later, we planted the native beech (fusca) and interplanted with kauri. We retained and fenced any patches of natives left over from the clearance” [the block had been cleared of most of its bush shortly before they purchased it].” The rest of the land was grazed, and there they encouraged a mixed sward, grazed the land lightly, established a slow-release fertiliser regime, and paid attention to the health of the soil.

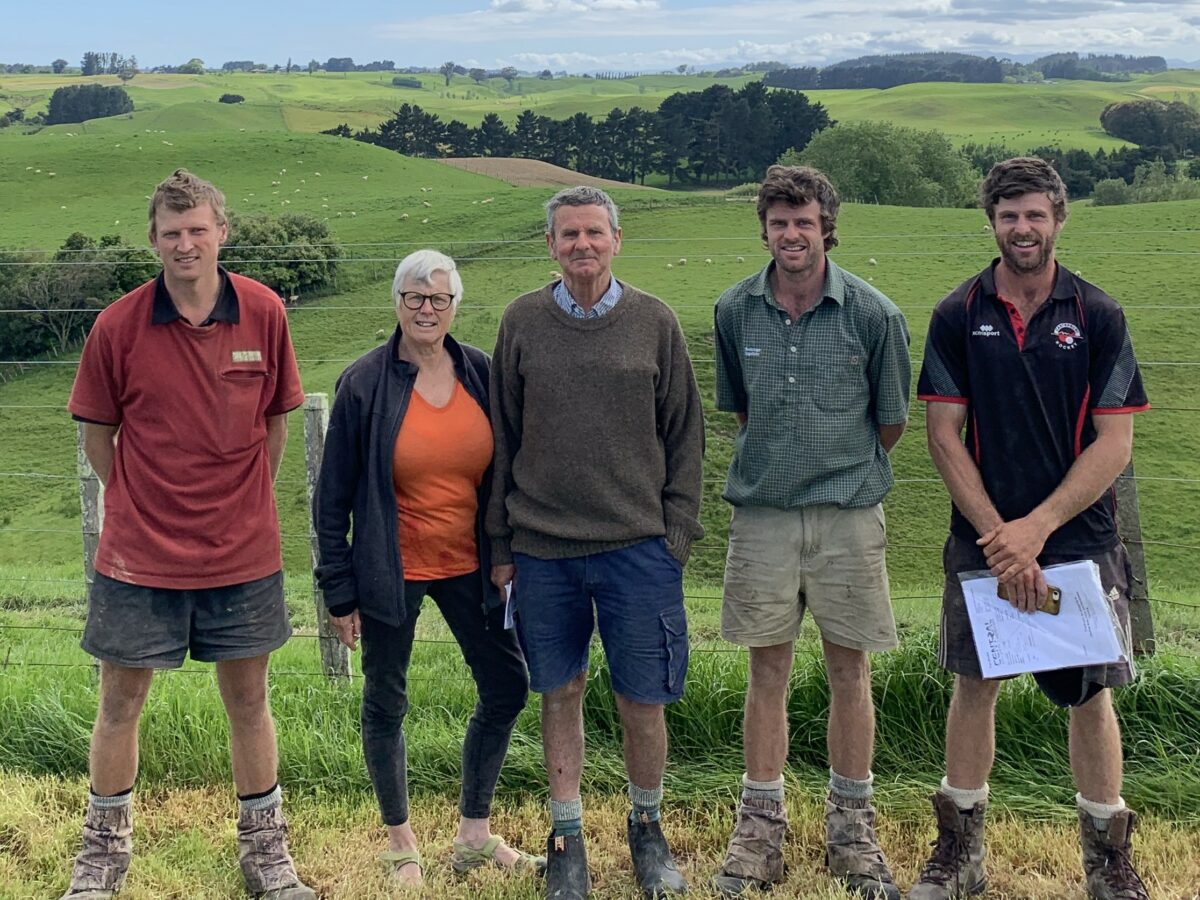

The farm continues to be run on these original principles by their grandson, Owen Saunders, and his wife Michelle. Gordon’s grandparents, Stanley and Elvira, farmed in North Lincolnshire at a farm called ‘Northlands’, and were of a similar innovative bent. They made all decisions on the farm with the latest farming methods in mind, from a careful rotation of crops and the integration of ‘farm-yard manure’ to monitoring each cow’s output so food could be rationed according to yield. And Stanley had good support from Elvira, who insisted their prize-winning dairy herd should be Friesians.

Tragically, Gordon’s father died when he was in his early forties and Gordon was just 10. But even in that short time his influence was felt. Gordon’s daughter, Janet Stephenson, says that Gordon put a lot of thought into what it meant to be a good farmer, and what he could do as a farmer that would make his dad proud.

That strong sense of environmental awareness runs deep and Janet has gone on to become a research professor at the University of Otago’s Centre for Sustainability Kā Rakahau o te ao Tūroa. Like the three generations before her, much of her research has been in energy, climate change, and people’s connections to the land.